- Home

- BLOG POST

- Contact Us

- HEADLINES NEWS STORIES

- SOCIAL MEDIA NEWS STORIES

- EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

- #2 HEADLINE NEWS STORIES

- RECOMMENDED BOOKS TO READ

- EXPERTS SPEAKERS VIDEOS

- EVENTS IN CALIFORNIA

- PAWS TO READ PROGRAM

- GGUSD & OCTA SAFE ROUTE

- #3 NEWS ARTICLES/RESOURCE

- #2 EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

- #3 EDUCATION RESOURCES

- #4 NEWS ARTICLES

- PODCAST RADIO/VIDEO

- ENVIRONMENTAL WELLNESS ED

- G.G. CA.CLIMATE CHANGE

- PDF BLOG POST FILES

- G.G. CONCEPT VETERAN DOG

- #3 HEADLINE NEWS STORYS

- HISTORY MILITARY WITH DOG

- #2 ABOUT HISTORY VETERANS

- BICYCLES /WALKING SAFETY

- #3 HISTORY VETERANS

- G.G. WAR DOG/K-9 PARK

- #4 VETERANS HISTORY

- RAIL TO TRAIL COVID 19

- PUBLIC RECORDS ACT GOV

- GARDEN GROVE DOWN TOWN

- #2 DOWN TOWN GARDEN GROVE

- BIKE PEDESTERIAN SAFTEY

- BLOG POST

- #2 GGUSD

- GARFFITI/BLIGHT OCTA/G.G.

- GARDEN GROVE SAFTEY

- EDUCATIONAL PDF DOCUMENTS

- GARDEN GROVE BIKE TRAIL

- CITY G.G. CA MEDAL BIKE

- MEMORAIL MEDAL OF HONOR

W.H.O. Says Limited or No Screen Time for Children Under 5 !

In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidelines that recommended no screen time other than video-chatting for children under 18 months. And it recommended introducing only “high-quality programming” to children 18 to 24 months of age, and advised that parents and caregivers watch the program with them. Children between the ages of 2 to 5 years should watch only one hour per day of approved programming.

“Early childhood is a period of rapid development and a time when family lifestyle patterns can be adapted to boost health gains,” said an official with the World Health Organization in a statement regarding new “screen time” guidelines.Credit...David Bagnall/Alamy

In a new set of guidelines, the World Health Organization said that infants under 1 year old should not be exposed to electronic screens and that children between the ages of 2 and 4 should not have more than one hour of “sedentary screen time” each day.

Limiting, and in some cases eliminating, screen time for children under the age of 5 will result in healthier adults, the organization, a United Nations health agency, announced on Wednesday

The Harmful Effects of Too Much Screen Time for KidsToday’s children have grown up with a vast array of electronic devices at their fingertips. They can't imagine a world without smartphones, tablets, and the internet. The advances in technology mean today's parents are the first generation who have to figure out how to limit screen time for children. While digital devices can provide endless hours of entertainment and they can offer educational content, unlimited screen time can be harmful.1 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends parents place a reasonable limit on entertainment media. Despite those recommendations, children between the ages of 8 and 18 average 7 ½ hours of entertainment media per day, according to a 2010 study by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. But it's not just kids who are getting too much screen time. Many parents struggle to impose healthy limits on themselves too. The average adult spends over 11 hours per day behind a screen, according to the

Today’s children have grown up with a vast array of electronic devices at their fingertips. They can't imagine a world without smartphones, tablets, and the internet.

The advances in technology mean today's parents are the first generation who have to figure out how to limit screen time for children. While digital devices can provide endless hours of entertainment and they can offer educational content, unlimited screen time can be harmful.1

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends parents place a reasonable limit on entertainment media. Despite those recommendations, children between the ages of 8 and 18 average 7 ½ hours of entertainment media per day, according to a 2010 study by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. But it's not just kids who are getting too much screen time.

Many parents struggle to impose healthy limits on themselves too. The average adult spends over 11 hours per day behind a screen, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

ADDRESS THE MENTAL HEALTH CRISS

As a business major, and then a practicing C.P.A., I never imagined that I would spend much of my time in public office focusing on the mental health crisis we are facing in the U.S. The importance of addressing mental illness hit me front and center five years ago when Kelly Thomas, who was schizophrenic, was killed in an incident with the Fullerton Police Department. Immediately after his death, the Orange County Board of Supervisors

Landmark Middle School’s top leaders replaced.

Streamed live on Oct 29, 2019 Board Meeting 10/29/19 PLEASE LISTEN TO PUBLIC COMMENTS STARTS AT 1:40:00 TO 2:31 HOUR BULLYING CONCERNS

HR 28,July 15, 2015 as amended, Dababneh. Sections 233.5 (part of the Hate Violence Prevention Act) and 60042 of the Education Code require instruction in kindergarten and grades 1 to 12, inclusive, to promote and encourage kindness to pets and humane treatment of animals;WHEREAS, Humane education programs seek to prevent violence by teaching empathy, compassion, and respect for all living beings and help children develop into caring, responsible citizens; and

Say something interesting about your business here.

Schools and school districts are undertaking steps to rectify these deficiencies by promoting humane education and implementing it in classrooms; now, therefore, be it

Resolved by the Assembly of the State of California, That compliance with Education Code provisions should include educating students on the principles of kindness and respect for animals and observance of laws, regulations, and policies pertaining to the humane treatment of animals, including wildlife and its environment; and be it further

Resolved, That actions such as implementing statewide or districtwide “humane education days” and involving nonprofit organizations in humane education activities with local faculty and school administrators be considered for inclusion in compliance efforts; and be it further

Family of Diego, boy who died after Landmark Middle School assault, takes legal action; says he was bulliedThe aunt and uncle of 13-year-old Diego Stolz, who died after being assaulted on campus Sept. 16, are seeking $100 million in damages

Juana Salcedo, aunt, and guardian of 13-year-old Diego Stolz, cries during a press conference in Riverside Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2019. The family announced that they have started legal proceedings against the Moreno Valley Unified School District following the on-campus assault on Sept. 16 at Landmark Middle School that led to Stolz’s death

40% of Muslim students surveyed in California say they’ve been bullied at school, report finds

Alham Elabed, whose son is Muslim and a special needs student at Redlands High School, speaks during a press conference Wednesday, Oct. 16, at the Council on American-Islamic Relations’ office in Anaheim. The organization released its biennial report on bullying of Muslim students in California. Elabed says her son was taunted and physically assaulted in May. His injuries required him to get two surgeries and continuing treatment, she said. (Photo courtesy of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, Los Angeles — CAIR-LA)

Can multimillion-dollar suicide awareness campaign lower Utah’s suicide rates?

SALT LAKE CITY — In the battle against the nation’s rising suicide rates, Utah leaders and donors met Monday to announce a “historic,” multimillion-dollar campaign to change stigmas surrounding mental health in the state.

“We’ve all had a personal journey with this issue. All of us have been impacted in some way, whether it’s family members, friends, loved ones, people in our community who have been impacted by suicide,” Lt. Gov. Spencer Cox said outside the state Capitol. “And so while we recognize that the government can’t solve all of our problems, there’s a critical role for government to play in this space.”

Two years ago, the Utah Department of Health released a report stating that teen suicides had increased 141% since 2011. A suicide prevention task force was then formed, Cox said. The idea for the campaign came out of that task force.

Last year, the Legislature provided $700,000 for the campaign if the public sector matched that amount in donations. Another $300,000 from the general fund was available for the campaign and did not require a match, Cox said.

Parents may fret, but teens and even experts say social media use has its benefits

Teenagers are constantly posting about what seems like near-perfect lives on social media sites, but looks can be deceiving.

In real life, their lives might not be so perfect.

Among social media's benefits is that it has allowed teenagers to connect all over the world. Still, the hours spent on Snapchat, Twitter, Instagram and other social media sites also have the potential to be harmful, child psychologists and therapists say.

Studies are increasingly showing links between an overuse of social media and a variety of health issues, such as anxiety and body image issues.

Seventy-five percent of teenagers in America today have profiles on social media sites, according to Common Sense Media. Some feel like they can’t live without it and may feel anxious if they can’t update their status or find out what their friends are doing. They may start to judge their self worth by how many Snapchat followers they have.

Weekly message from Cypress Church: Empathy is loving !!

Weekly message from Cypress Church: Empathy is loving our neighbors Galatians 6:2 Bear one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ.

I love going to my wife’s kindergarten classroom. Not only to see the amazing way she teaches young minds, but also how she creates a kind, compassionate, empathetic environment for children. When a child is hurting she stops all the kids involved or the whole class and as a group they talk out how it feels when you feel hurt, and then figure out how to help the person in need. She does this enough to where kids automatically show empathy. One child had forgotten their snack and someone noticed and asked Kristi if she could share her snack because she remembered what it felt like to have forgotten her own snack one day. That’s empathy at it’s finest.

Fred Rodgers of the long lasting PBS series Mr. Rogers Neighborhood was a child advocate. Last year a documentary was made of about him called Won’t You Be My Neighbor? This year a movie is being made called A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, which stars Tom Hanks. In both of these productions, the major traits brought out were Fred Rogers’ radical kindness and empathy. He did not just feel for people, he sought to understand them and, in a sense, walk in their pain or circumstance. The Fred Rogers Center has as one of their core values, empathy, stating, “We know that understanding and compassion are fundamental to children’s healthy social and emotional development.” Empathy is fundamental for all humanity. It’s key to our living in society and paramount in Jesus’ command to love our neighbor Matthew 22:39.

Parents may fret, but teens and even experts say social media use has its benefits

Asha Davis and Erin Burnett, Special to USA TODAY

Teenagers are constantly posting about what seems like near-perfect lives on social media sites, but looks can be deceiving.

In real life, their lives might not be so perfect.

Among social media's benefits is that it has allowed teenagers to connect all over the world. Still, the hours spent on Snapchat, Twitter, Instagram and other social media sites also have the potential to be harmful, child psychologists and therapists say.

Studies are increasingly showing links between an overuse of social media and a variety of health issues, such as anxiety and body image issues.

TEACHING EMPATHY GO A LONG WAYS TO STOP BULLYING!

District Replaces Principal After Fatal Sucker-Punch of 13-Year-Old Boy at Moreno Valley School

District Replaces Principal After Fatal Sucker-Punch of 13-Year-Old Boy at Moreno Valley School

District Replaces Principal After Fatal Sucker-Punch of 13-Year-Old Boy at Moreno Valley School

District officials have replaced administrators at a Moreno Valley middle school where a boy died after being assaulted by two other students.

The Press-Enterprise reports Thursday that the Moreno Valley Unified School District is replacing Principal Scott Walker and Assistant Principal Kamilah O’Connor at Landmark Middle School.

The new principal, Rafael Garcia, was the district’s coordinator for child welfare and attendance.

Landmark Middle School’s top leaders replaced, six weeks after Diego’s death

District Replaces Principal After Fatal Sucker-Punch of 13-Year-Old Boy at Moreno Valley School

District Replaces Principal After Fatal Sucker-Punch of 13-Year-Old Boy at Moreno Valley School

Principal Scott Walker and Assistant Principal Kamilah O’Connor are out; Rafael Garcia named principal

Moreno Valley Unified has replaced both top administrators at Landmark Middle School, where a boy died after being assaulted by two other students in September.

Replacements for Principal Scott Walker and Assistant Principal Kamilah O’Connor were announced at the Tuesday, Oct. 29, school board meeting. O’Connor’s name was listed a day earlier in a legal filing that alleged that she ignored a complaint of bullying that led to the death of eighth grader Diego Stolz last month.

Superintendent Martinrex Kedziora and the school board “want to provide students with the best academic, social and emotional experience while they are in our schools,” a Moreno Valley Unified School District statement released Wednesday said. “They understand that each school has unique needs, and we want to better address those needs at each school.”

Starting Wednesday, Landmark’s new principal is Rafael Garcia. He had been the district’s coordinator for child, welfare and attendance. Before joining the district in 2016, Garcia worked for the Val Verde Unified School District, including jobs as an interim and assistant

A boy is dead after a beating at school. Classmates say he was the target of bullies.

District Replaces Principal After Fatal Sucker-Punch of 13-Year-Old Boy at Moreno Valley School

Moreno Valley Boy Told Administrator About Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

September 26, 2019 at 1:29 p.m. PDT

A 13-year-old California boy has died more than a week after being punched in an attack by two boys that was caught on video.

The middle school teen — who has been identified only by his first name, Diego — was pronounced clinically dead on Tuesday night, the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department said in a statement. Diego had been hospitalized since the Sept. 16 attack at Landmark Middle School in Moreno Valley, Calif., roughly 65 miles east of Los Angeles. The sheriff’s department said Diego’s family will donate the boy’s organs “to transform this tragedy into the gift of life for other children.”

Students confront superintendent after Calif. boy dies after school beatingDiego, 13, died outside his Moreno Valley, Calif., school on Sept. 16 after being punched during a fight. Students and parents confronted the superintendent. (Moreno Valley Students Matter/Facebook)

Families in the 33,000-student Moreno Valley Unified School District reacted with grief and outrage after the attack. Parents and students gathered last Friday in a “Ditch for Diego” protest that went from a nearby community park to the district’s registration office. Diego’s death Tuesday night prompted more memorials, vigils — and heated confrontations with district officials whom some parents and students accused of mishandling what they call a pervasive bullying problem.

Moreno Valley Boy Told Administrator About Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

2 defendants accused of killing Landmark Middle School student Diego Stolz released from custody

Moreno Valley Boy Told Administrator About Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

.jpg/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:388,h:194,cg:true)

Days before he was fatally attacked at his middle school in September, 13-year-old Diego Stolz told an administrator that he was being bullied by other students.

Diego Stolz is seen in a photo tweeted out by a family member.

But Landmark Middle School officials did nothing, and the boy was assaulted and killed by the same classmates at the Moreno Valley campus, according to an attorney for the victim’s family.

A legal claim against Moreno Valley Unified School District was filed last Friday by Juan and Felipe Salcedo, Diego’s aunt and uncle who raised him from the age of 1 following his mother’s death.

On Tuesday, attorney Dave Ring announced the claim, a precursor to a wrongful death lawsuit.

Family of boy killed during bullying at MoVal school announce lawsuit

2 defendants accused of killing Landmark Middle School student Diego Stolz released from custody

2 defendants accused of killing Landmark Middle School student Diego Stolz released from custody

The family of a 13-year-old boy who was fatally injured during a confrontation with two classmates on a Moreno Valley middle school campus announced today they’re suing the Moreno Valley Unified School District for wrongful death and civil rights violations, alleging their pleas to address bullying of the teen were largely ignored.

“This family did all the right things. They went in and complained and did everything right. But the school failed them,” attorney David Ring told reporters during a news briefing at the Mission Inn Hotel & Spa in Riverside. “The administration could have prevented this from happening, and they blew it.”

Ring, who was retained by the legal guardians of the victim, Diego Stolz, filed a tort claim in Riverside County Superior Court, seeking damages and “equitable relief” -- policy changes -- from MVUSD.

The damage award being sought, which Ring acknowledged is an unsettled figure that will likely change, is $100 million.

2 defendants accused of killing Landmark Middle School student Diego Stolz released from custody

2 defendants accused of killing Landmark Middle School student Diego Stolz released from custody

2 defendants accused of killing Landmark Middle School student Diego Stolz released from custody

uana Salcedo, aunt and guardian of 13-year-old Diego Stolz, cries as she sits next to the family’s attorney David Ring during a press conference in Riverside Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2019. One of the defendants in Diego’s death was released to home custody Friday, Nov. 1

mber 1, 2019 at 6:06 pm | UPDATED: November 1, 2019 at 6:06 pm

The two defendants in the deadly assault of Landmark Middle School student Diego Stolz were released to home custody Friday, Nov. 1, attorneys say.

Attorneys for the two 13-year-old boys say Riverside County Superior Court Judge Roger Luebs weighed factors including family support, an “exceptional” behavior report for his time in Juvenile Hall, and the absence of any prior juvenile offenses.

Prosecutors charged the two with voluntary manslaughter and assault by means of force likely to produce great bodily injury after saying one of them suddenly punched Stolz, who had been standing with his hands at his side, and knocked Stolz’s head against a column. Stolz fell to the ground, but the two continued attacking him, a video shows.

Eighth-grader’s family complained of bullying days before fatal assault, legal claim states

Moreno Valley Student’s Family Complained of Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

Moreno Valley Student’s Family Complained of Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

OCT. 29, 2019 4 AM

On a Friday in mid-September, Diego Stolz’s adult cousin accompanied him to a meeting with the assistant principal at Landmark Middle School in Moreno Valley.

The eighth-grader had been repeatedly targeted by bullies. The day before, one of them had punched him in the chest and threatened that more violence was coming.

Stolz was scared.

The assistant principal, Kamilah O’Connor, assured him that the bullies would be suspended for three days, starting Monday, and told him he could miss the remainder of the school day.

But when the 13-year-old returned to classes after the weekend, the boys were still there.

They confronted him around lunchtime with a pair of sucker punches that knocked him to the ground. The blows were captured on cellphone video that was posted to Facebook.

Stolz never woke up. He was removed from life support nine days later.

Those are the allegations outlined in a legal claim filed Monday against the Moreno Valley Unified School District on behalf of Stolz’s aunt and uncle, Juana and Felipe Salcedo. The couple raised Stolz as their own after both of his parents died.

Moreno Valley Student’s Family Complained of Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

Moreno Valley Student’s Family Complained of Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

Moreno Valley Student’s Family Complained of Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

Days before he was fatally attacked at Landmark Middle School in September, Diego Stolz told an administrator that he was being bullied by other students.

Diego Stolzis seen in a photo tweeted out by a family member.

But the Moreno Valley school did nothing, and the 13-year-old was assaulted and killed by the same classmates, according to an attorney for the victim’s family.

The legal claim against the Moreno Valley Unified School District was filed last Friday by Juan and Felipe Salcedo, Diego’s aunt and uncle who raised him from the age of 1 following his mother’s death.

On Tuesday, attorney Dave Ring announced the claim, a precursor to a wrongful death lawsuit.

The claim alleges Diego and his adult cousin Jazmin sought help from Landmark’s assistant principal on Sept. 13, one day after he was targeted by bullies and “verbally and physically” harassed.

The bullies were a group of boys who had previously been friends with Diego, then -- for unknown reasons -- turned on him during the seventh grade, according to Ring.

Diego met with the assistant principal alone for 20 minutes. When the meeting was over, she told Jazmin the bullies would be suspended for three days, beginning Sept. 16, and that their class schedules would be changed, according to the claim.

She also told Diego he could miss school that day, a Friday, and return Monday, the document states.

Teen's Family Says He Complained of Bullying Before Death

Moreno Valley Student’s Family Complained of Bullying Days Before Fatal Sucker Punch: Legal Claim

Moreno Valley parents seek solutions to campus bullying, violence after Landmark Middle School boy’s

Diego Stolz, 13, died after being attacked on Sept. 16, 2019 at Landmark Middle School in Moreno Valley by two other boys.

The family of a 13-year-old says he complained to an administrator that he was being bullied at his Southern California middle school days before the assault that killed him.

Juana and Felipe Salcedo, the aunt and uncle of Diego Stolz who raised the boy since his parents died, filed a legal claim against the Moreno Valley Unified School District, the family's attorney said in a news conference Tuesday morning.

David Ring, the family attorney, said Diego was a good kid who just wanted to go to school and learn.

"He was a normal 13-year-old boy," Ring said. "He liked hiking. He liked his mom's food. He liked going to class and learning."

The claim, which lists damages of $100 million, said Stolz and an adult cousin met with a Landmark Middle School assistant principal in September after he was targeted by bullies and punched at the school 65 miles east of Los Angeles.

They were told the bullies would be suspended, but when Stolz returned to school after the weekend they confronted and punched him, knocking him to the ground, according to the claim.

Stolz was removed from life support and died nine days later.

Anahi Velasco, a Moreno Valley Unified spokeswoman, said the district doesn't believe it is liable for Stolz's death. She declined to comment on the pending litigation or release details about the case.

"To be clear, there is no place for bullying in our schools and acts of violence will not be tolerated," she said.

Two boys have been charged with manslaughter in connection with Stolz's death. They have denied the allegations and are due to appear in juvenile court on Friday.

Earlier this month, two girls were arrested at another school in the district after allegedly assaulting another student during lunch.

Moreno Valley parents seek solutions to campus bullying, violence after Landmark Middle School boy’s

Moreno Valley parents seek solutions to campus bullying, violence after Landmark Middle School boy’s

Moreno Valley parents seek solutions to campus bullying, violence after Landmark Middle School boy’s

The aunt and uncle of 13-year-old Diego Stolz, who died after being assaulted on campus Sept. 16, are seeking $100 million in damages Juana Salcedo, aunt, and guardian of 13-year-old Diego Stolz, cries during a press conference in Riverside Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2019. The family announced that they have started legal proceedings against the Moreno Valley Unified School District following the on-campus assault on Sept. 16 at Landmark Middle School that led to Stolz’s death.

‘Out Of Control’: Girls Brawl In Classroom In Latest Fight At Moreno Valley School

Moreno Valley parents seek solutions to campus bullying, violence after Landmark Middle School boy’s

‘Out Of Control’: Girls Brawl In Classroom In Latest Fight At Moreno Valley School

MORENO VALLEY (CBSLA) — Another shocking video of students fighting at a Moreno Valley school has surfaced online, within the same district where a 13-year-old boy died from being sucker punched during a fight in the yard of Landmark Middle School.

The video was posted to Facebook and shows a loud melee of screaming girls in a classroom at Sunnymead Middle School.

In the video, the girls are screaming, grappling and fighting. Girls are seen throwing punches and wrestling each other to the ground. It appears a teacher tries to get into the middle of the melee and separate the fighting girls, but asks another student to go and get help.

Student Delilah Barraza says she doesn’t know the girls involved in Wednesday’s fight, but she still feels apprehension, saying “I got very scared, because the school is starting to get out of control with the fights.”

School officials from Sunnymead Middle School confirmed that a physical altercation happened Wednesday between two 12-year-old girls inside a classroom. One of the students sustained a non-life-threatening injury but did not need hospitalization.

“The other student was determined the aggressor and charges will be filed out of custody,” the statement from Sunnymead Middle School said.

Schools Superintendent Dr. Martinrex Kedziora held a late afternoon news conference in which he assured parents the district was taking all precautions with the safety of its students.

Moreno Valley parents seek solutions to campus bullying, violence after Landmark Middle School boy’s

‘Out Of Control’: Girls Brawl In Classroom In Latest Fight At Moreno Valley School

EDUCATION NEWS STORIES !!

Kids First: Youth Suicide Prevention | FOX59

New health report for California shows 34% increase in teen suicide and 29% rise in childcare costs

Chino Valley Unified reveals 4 teachers had sex with students

Ontario-Montclair School District family & Collaborative Services Clinical Supervisor Jose A. Gonzalez speaks during a suicide prevention workshop for parents and students at Hill Auditorium in Ontario on Wednesday, Sep 11, 2019. (Photo by Terry Pierson, The Press-Enterprise/SCNG)

By Beau Yarbrough | byarbrough@scng.com | Inland Valley Daily BulletinPUBLISHED: September 23, 2019 at 6:00 am | UPDATED: October 1, 2019 at 10:17 am

Sep 09, 2019 · INDIANAPOLIS -- September is National Suicide Prevention Month. In Fox59's Kids First segment this month, we are learning how you can help save the life of a young person. Sadly, 1 in 5 …

Chino Valley Unified reveals 4 teachers had sex with students

New health report for California shows 34% increase in teen suicide and 29% rise in childcare costs

Chino Valley Unified reveals 4 teachers had sex with students

By Sandra Emerson | semerson@scng.com | September 3, 2012 at 12:00 am

Special Section: Safe Schools

Four teachers in the Chino Valley Unified School District have been involved in sexual relations with students in recent years, according to documents provided by the district.

Three of the four teachers allegedly involved in sexual relationships with students were arrested, and two of them pleaded guilty to criminal charges.

There were 10 documented cases of teacher misconduct of all kinds since the 2005-06 academic year.

Eight of the 10 teachers resigned and one temporary teacher was released. The 10th case is ongoing.

The school district provided the documents in response to a Public Records Act request made by the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, The Sun and Redlands Daily Facts.

The newspapers are compiling a Safe Schools special report, requesting documents from 19 school districts concerning complaints of teacher misconduct.

The district redacted the teachers’ names in the records provided to the Daily Bulletin, but the records of two cases match those of two Chino Hills High School teachers who pleaded guilty in 2011 for having a sexual relationship with a student during the 2009-10 school year.

One of the cases involved Chino Hills High School science teacher John Hirsch, who pleaded guilty in March 2011 to unlawful sexual intercourse and committing a lewd act upon a child.

The student involved with Hirsch filed a lawsuit against the school district in June 2011, which is still ongoing.

New health report for California shows 34% increase in teen suicide and 29% rise in childcare costs

New health report for California shows 34% increase in teen suicide and 29% rise in childcare costs

New health report for California shows 34% increase in teen suicide and 29% rise in childcare costs

Sandy Thornton looks at some of the dozens of silhouetttes that represented young people who committed suicide because of bullying. The Ability Awareness Project held an event at Main Beach, Laguna Beach on Oct. 7. On display were dozens of images of children who lost their lives due to bullying.

A new national report focusing on women’s and children’s health has found a 34% increase in teen suicides among California youth between the ages of 15 and 19 over the past three years — significantly higher than the national increase of 25% — and a 29% surge in infant childcare costs during the same period.

The report, titled America’s Health Rankings 2019, was released by the United Health Foundation, a philanthropic nonprofit that aims to expand healthcare access.

While this report has been published for 30 years, researchers have taken a deeper dive into women’s and children’s health over the past three years, said Dr. Janice Huckaby, chief medical officer for maternal-child health strategy at Optum Healthcare Solutions in Baltimore.

The 34% increase in teen suicides over the past three years in California is “deeply troubling,” Huckaby said.

What you can and cannot expect from California’s new mental health line

What you can and cannot expect from California’s new mental health line

New health report for California shows 34% increase in teen suicide and 29% rise in childcare costs

The state is spending $10.8 million over three years on the project

This month, California launched the first statewide mental health line. The peer-run line based in San Francisco will get $10.8 million over three years to expand across the state.

‘Warm Line’

Approximately 1 in 5 adults in the U.S. – 43.8 million – experience mental health challenges per year. This month, the state signed off on funding for a call center based in San Francisco to cover the whole state. The California Peer-Run Warm Line offers free nonemergency emotional support and referrals via phone or instant messaging. Its toll-free number is 855-845-7415 and it operates 7 a.m.-11 p.m. Mondays-Fridays, 7 a.m.-3 p.m. Saturdays and 7 a.m.-9 p.m. Sundays.

Mark Salazar, executive director of the Mental Health Association of San Francisco, says, “The call center is scheduled to ramp up to 24/7 service by the end of the year and expects about 25,000 calls a year. San Francisco has operated a similar service since 2014.”

On the line

When Salazar described the service, he said, “Our goal is to offer accessible, relevant, nonjudgmental peer support to anyone in the state of California who reaches out to us. Having readily available access to support and human connection helps people avoid getting to a crisis point later on.

“Callers consistently reach out to the Warm Line for multiple, often related, reasons. Someone who calls feeling isolated, for example, may also be experiencing underlying mental health challenges that create barriers to employment and accessing stable housing. We regularly see examples of the cycle of trauma being perpetuated in this way, often putting people in danger of reaching a crisis point without ongoing support.”

The Problem With Rich Kids

What you can and cannot expect from California’s new mental health line

These three suicide-prevention bills are now law in California

In a surprising switch, the offspring of the affluent today are more distressed than other youth. They show disturbingly high rates of substance use, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, cheating, and stealing. It gives a whole new meaning to having it all.

By Suniya S. Luthar Ph.D., published November 5, 2013 - last reviewed on June 9, 2016

It is widely accepted in America that youth in poverty are a population at risk for being troubled. Research has repeatedly demonstrated that low family income is a major determinant of protracted stress and social, emotional, and behavioral problems. Experiencing poverty before age 5 is especially associated with negative outcomes.

But increasingly, significant problems are occurring at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum, among youth en route to the most prestigious universities and well-paying, high-status careers in America. These are young people from communities dominated by white-collar, well-educated parents. They attend schools distinguished by rich academic curricula, high standardized test scores, and diverse extracurricular opportunities. The parents' annual income, at $150,000 and more, is well over twice the national average. And yet they show serious levels of maladjustment as teens, displaying problems that tend to get worse as they approach college

These three suicide-prevention bills are now law in California

What you can and cannot expect from California’s new mental health line

These three suicide-prevention bills are now law in California

They require plans for kindergarten through 12th grade, online posting of anti-bullying policies and money for a suicide-prevention fund

ED: October 15, 2019 at 6:00 am | UPDATED: October 15, 2019 at 9:58 am

Gov. Gavin Newsom has signed all three bills passed by the California legislature this year aimed at reducing bullying and teen suicide.

“As responsible adults, we must be sensitive to the difficulties young people face and provide assistance as they navigate adolescence,” Assemblyman James Ramos, D-Highland, is quoted as saying in a news release issued Thursday, Oct. 10, after Newsom signed Ramos’ Assembly Bill 1767. “Offering age appropriate suicide prevention education is one of the ways we can connect the community and create a culture of positive mental health outcomes.”

The newly signed bill builds on AB 2246, approved in 2016, which required school districts to have a suicide-prevention policy that addresses the needs of their highest-risk students in seventh through 12th grades. Former Gov. Jerry Brown signed AB 2639 in 2018. That bill required districts to update those policies every five years. Ramos’ new bill requires districts serving kindergarten through sixth grades to create suicide-prevention policies.

AB 1767 was the second of two suicide-related bills Ramos introduced this year.

AB 34, the first bill he introduced as an assemblyman, attempts to tackle one of the issues youth face that experts have linked to suicide – bullying. It requires school districts to post bullying prevention policies online as well as information about cyber bullying. Newsom signed it Sept. 12.

On Wednesday, Oct. 2, Newsom signed AB 984, authored by Assemblyman Tom Lackey, R-Palmdale. The bill allows taxpayers to send their excess tax payments to a new Suicide Prevention Voluntary Contribution Fund. The fund would award grants and help fund crisis centers that are active members of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

HOPE4UTAH.COM SUICDE PREVENTION!!!

Here’s what 4 California school districts did to reduce the number of students contemplating suicide

Here’s what 4 California school districts did to reduce the number of students contemplating suicide

Here’s what 4 California school districts did to reduce the number of students contemplating suicide

Santa Ana Unified School District students participating in the We Care campaign by encouraging peers to “get help” form a heart in a kick-off event for the program at the start of the 2018-19 school year.

It takes a village to lower the number of young people who think about killing themselves, according to educators whose school districts have dramatically reduced suicide ideation rates among their student populations.

In four such school districts in Southern California, the number of students who contemplated suicide fell dramatically when the districts partnered with local government agencies and nonprofits to educate students, their teachers and others on campuses about warning signs and how to help those in crisis.

About 70% of the state’s 1,026 school districts give their students the California School Climate, Health, and Learning Surveys (CalSCHLS), which are meant to gauge how many ninth- and 11th-graders and students in non-traditional high schools have considered suicide, as well as poll their experiences with drugs, bullying, whether they’ve seen a weapon on campus, and more.

San Francisco-based WestEd, which distributes and tabulates the CalSCHLS surveys, does not make site-level data available to the public or media. A Southern California News Group analysis, which averaged district-level data from 2013-14 through the 2016-17 school years, showed that about 18% of students surveyed had expressed suicidal thoughts.

Four school districts stood out in the SCNG analysis, showing drops in suicidal ideation rates among students in the same graduating classes over the four-year period.

We Care. Get Help. [SAUSD Mental Health Assistance Awareness Video]

Here’s what 4 California school districts did to reduce the number of students contemplating suicide

Here’s what 4 California school districts did to reduce the number of students contemplating suicide

We Care. Get Help. [SAUSD Mental Health Assistance Awareness Video] Created for Behavioral and Emotional Counseling/Pupil Support Services Department at Santa Ana Unified School District by Kinder Future (Lindsey Etheridge and Lisa Shih) www.kinderfuture.co . Ask your teacher or school office for more information, and always reach out when you feel the need to express your feelings.

From sau.pham@sausd.us on January 25th, 2018

Let’s look up: Responding to Orange County’s latest teen suicide tragedy

Here’s what 4 California school districts did to reduce the number of students contemplating suicide

Let’s look up: Responding to Orange County’s latest teen suicide tragedy

Police investigating at Don Juan Avila elementary and middle schools in Aliso Viejo after an apparent suicide early Tuesday, March 5, 2019. (Photo Courtesy OC Sheriff’s Department)

By RONNETTA JOHNSON | Orange County RegisterPUBLISHED: March 14, 2019 at 12:42 pm | UPDATED: March 14, 2019 at 12:42 pm

The recent local headline brought tears to my eyes. Our Orange County community lost a 13-year-old boy from an apparent suicide on an elementary and middle school campus, in the morning hours before school bells rang. A family lost a son, and a school day was forever scarred with tragedy. Another life has been cut short, the details we may never fully understand.

As the community mourns with this family, the heartbreak is added to a growing list of teen suicides—seen not just in headlines, but on the most popular shows our kids watch on Netflix, in the lives of notable celebrities, too. Suicide is on the rise across the nation and it can happen to anyone.

In Orange County, the data is certainly alarming. Since the late 1990s, Orange County has had the largest suicide rate increase among the nation’s 20 most populous counties, according to an analysis of federal suicide data by Voice of OC. It is the second leading cause of death among 10 to 24-year-olds and the Orange County Health Care Agency reported that for each suicide death in the county, there are 10 hospitalizations for attempted suicides or intentional self-injuries. A new report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that suicide rates for adolescent boys and girls in the U.S. have been steadily on the rise since 2007, with rates for girls 15 to 19 doubling from 2007 to 2015.

We know that kids of all ages tackle the daily stresses of grades, expectations to succeed, the need to fit in and the presence of bullies.

Teen suicide is on the rise and this is why

bullying led to yucaipa teen's suicide and contributed to suicidal thoughts in other students

Let’s look up: Responding to Orange County’s latest teen suicide tragedy

Every 40 seconds, another human life is taken by suicide, according to World Health Organization data.

In Canada, a new report reveals that young people between the ages of 15 and 19, who are struggling with mental illness and addiction, have the highest rates of suicide attempts. Middle-aged men are also at high risk, as are children and youth in First Nations communities who live with the legacy of trauma perpetuated by colonization and the residential school system.

World Suicide Prevention Day this Sunday provokes us to pay attention. Suicide is a silent epidemic that ruins lives and devastates families and communities. As a researcher, I have been examining and researching the factors that contribute to the blossoming of human potential, and the factors that undermine its full realization, for close to two decades. Suicide is the ultimate subversion of human potential.

Why are so many teenagers taking their own life? One factor is what I call “toxic socialization” — a process of physical or emotional childhood and adolescent abuse. Those who grow up in toxic environments are up to 12 times more likely to experience addiction, depression and to try to commit suicide.

bullying led to yucaipa teen's suicide and contributed to suicidal thoughts in other students

bullying led to yucaipa teen's suicide and contributed to suicidal thoughts in other students

bullying led to yucaipa teen's suicide and contributed to suicidal thoughts in other students

bullying led to yucaipa teen's suicide and contributed to suicidal thoughts in other students ,lawsuits allege

Lawyer files 6th lawsuit against Yucaipa-Calimesa school district over bullying

bullying led to yucaipa teen's suicide and contributed to suicidal thoughts in other students

bullying led to yucaipa teen's suicide and contributed to suicidal thoughts in other students

Yucaipa-Calimesa Joint Unified School District has been hit with a sixth lawsuit over allegations that it’s endangering students by not taking bullying seriously.

“This is the sixth lawsuit that we have had to file against this hapless school district,” Pasadena attorney Brian Claypool said at a news conference Tuesday, June 25, announcing the lawsuit.

“Six lawsuits against the same school district because they simply do not take bullying seriously,” Claypool said. “Kids continue to get injured and beaten up at their schools. Four of the cases that we have right now against this school district involve students who have been physically assaulted. The fifth student is dead. The sixth student was mentally traumatized so much that she was suicidal.”

Claypool filed a notice of claim with the courts on Monday, he said, and notified the school district of the coming lawsuit.

Downloads 2019 California Youth Mental Health and Resource

California Youth Mental Health

LADY GAGA’S BORN THIS WAY FOUNDATION AND CALIFORNIA’S MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES OVERSIGHT AND ACCOUNTABILITY COMMISSION RELEASE RESULTS OF CALIFORNIA YOUTH MENTAL WELLNESS SURVEY

Study Finds 1 in 3 California Youth Lack Reliable Access to Mental Health Resources (Click here to view report)

May 28, 2019 – Today, Lady Gaga’s Born This Way Foundation and California’s Mental Health Services Oversight & Accountability Commission (MHSOAC) released “California Youth Mental Health: Understanding Resource Availability and Preferences,” a survey of more than 400 young people in California ages 13 to 24 exploring how they view their own mental wellness, their access to key mental health resources and what they want those resources to look like, and the mental health innovations they want to see in the state.

Overall, the survey paints a portrait of youth who care about their mental wellness and recognize it as a priority, but who lack access to the resources they need to support and maintain it. Key findings of the survey include:

- 9-in-10 young people say mental health is a priority, but only 4-in-10 rate their own mental health highly. Additionally, a majority (54%) say they have felt stressed frequently in the past month and approximately a third felt helpless or sad (35%) or fearful (30%).

- Approximately 1-in-3 young people say they lack reliable access to resources to support their mental wellness or address a mental health issue and are even less likely to say they have the resources to deal with many serious but common situations. For example, about half of youth say they would not have the resources needed if they felt suicidal (55%) or felt like harming themselves (54%).

- Youth cite knowing where to go and cost as their key barriers to mental health resources. Nearly half say that young people in their city “don’t know where to go” (48%) or “can’t afford the cost” (36%) of mental health resources.

- While young people struggle to access mental health resources, they are open to using a wide variety of them and they want to learn skills to support their mental wellness. Encouragingly, most (81%) say they are interested in learning coping skills and tools to deal with the stresses of everyday life and that they would be comfortable using a variety of resources such as classes that teach skills to support mental wellness (66%).

- California youth see improving access to care as the top priority for the state’s mental health system. More than a third (35%) say innovations that address this issue should be the biggest priority for the state’s system.

https://www.mhsoac.ca.gov/2019-california-youth-mental-health-wellness-survey-results-press-release

HUMANE EDUCATION TO TEACH EMPATHY BAN SMART PHONES !!!

GAMING,SOCIAL MEDIA AND MENTAL WELLNESS PRESENTED BY SINA SAFAHEIM M.D.

GAMING,SOCIAL MEDIA AND MENTAL WELLNESS PRESENTED BY SINA SAFAHEIM M.D.

GAMING,SOCIAL MEDIA AND MENTAL WELLNESS PRESENTED BY SINA SAFAHEIM M.D.

BY HOAG HOSPITAL CALIF NEWPORT BEACH.

Student to Sue Yucaipa School District bullying

GAMING,SOCIAL MEDIA AND MENTAL WELLNESS PRESENTED BY SINA SAFAHEIM M.D.

GAMING,SOCIAL MEDIA AND MENTAL WELLNESS PRESENTED BY SINA SAFAHEIM M.D.

The family of a 15-year-old girl filed a claim Monday against the Yucaipa-Calimesa Joint Unified School District alleging the district could have prevented a brutal caught-on-video beating on school campus. Kareen Wynter reports for the KTLA5 News at 3 on June 25, 2019. Show more

Parents sue school district after their severely bullied 13-year-old

GAMING,SOCIAL MEDIA AND MENTAL WELLNESS PRESENTED BY SINA SAFAHEIM M.D.

The Wait Until 8th pledge empowers parents to rally together to delay giving children a smartphone

Parents sue school district after their severely bullied 13-year-old daughter hanged herself and left behind note 'apologizing for being ugly'

- Rosalie Avila, 13, hanged herself November 28 after being bullied for two years

- Her parents Freddie and Charlene were being cyber bullied over social media

- Someone sent them a crude photo mocked up with an image of Rosalie next to a grave, saying 'hey mom, bury me in here'

- Rosalie wrote an apology note to her family and said she was 'ugly' and a 'loser'

- She was in the 8th grade at Mesa View Middle School in Yucaipa, California

- Her parents have filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the school district

- They claim they repeatedly contacted district about the verbal abuse she was subjected to and told administrators that as a result she had begun to cut herself

The Wait Until 8th pledge empowers parents to rally together to delay giving children a smartphone

The Wait Until 8th pledge empowers parents to rally together to delay giving children a smartphone

The Wait Until 8th pledge empowers parents to rally together to delay giving children a smartphone

The Wait Until 8th pledge empowers parents to rally together to delay giving children a smartphone until at least 8th grade. By banding together, this will decrease the pressure felt by kids and parents alike over the kids having a smartphone.

Smartphones are distracting and potentially dangerous for children yet are widespread in elementary and middle school because of unrealistic social pressure and expectations to have one.

These devices are quickly changing childhood for children. Playing outdoors, spending time with friends, reading books and hanging out with family is happening a lot less to make room for hours of snap chatting, instagramming, and catching up on You Tube.

Parents feel powerless in this uphill battle and need community support to help delay the ever-evolving presence of the smartphone in the classroom, social arena and family dinner table. Let’s band together to wait until at least eighth grade before children are allowed to have a smartphone.

Therapy dogs get "married" in Texas hospital wedding ceremony

The Wait Until 8th pledge empowers parents to rally together to delay giving children a smartphone

Therapy dogs get "married" in Texas hospital wedding ceremony

MANSFIELD, Texas (KABC) -- Here comes the bride - on all four legs.

A pair of therapy dogs tied the knot in Texas. The two Golden Retriever pooches work together at Methodist Mansfield Medical Center's Physical Medicine Department near Dallas. Peaches and Duke sparked a romance by splitting a Puppuccino at the hospital's Starbucks. They like to snuggle with each other and are often seen kissing, so a wedding seemed like the appropriate next step.

One of the hospital's pastors officiated the service. As with any traditional ceremony, the bride and groom dressed in their best wedding attire. Peaches even wore a garter on her paw. The two then enjoyed some wedding cake at a reception and took pictures like any happily married couple.

Peaches and Duke help patients focus on their rehabilitation. Even the simple act of petting a dog can help patients improve their strength and range of motion.

The powerful prescription of pets

The Wait Until 8th pledge empowers parents to rally together to delay giving children a smartphone

Therapy dogs get "married" in Texas hospital wedding ceremony

Sure, you love your pet. What may surprise you is how your pet loves you back.

A survey found 97 percent of physicians believe there are health benefits to having a pet, mental as well as physical. Check out this video — created in partnership with Mason Turner, MD, psychiatrist and director, Outpatient Mental Health and Addiction Medicine, Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California — about what powerful medicine our pets can provide.

Not ready to commit to a pet? Humans are good for you, too.

Results Show 75% of Doctors said Patients’ Health Improved as the Result of Getting a Pet

Washington, D.C. (October 27, 2014) — The Human Animal Bond Research Initiative (HABRI) Foundation, today released the results of a first-of-its-kind survey detailing the views of family physician on the benefits of pets to human health.

“Doctors and their patients really understand the human health benefits of pets, and they are putting that understanding into practice” said HABRI Executive Director Steven Feldman. “The Human Animal Bond Research Initiative funds research on the evidence-based health benefits on humananimal interaction, and this survey demonstrates that we are on the right track.”

HABRI partnered with Cohen Research Group to conduct an online panel survey of 1,000 family doctors and general practitioners. This is the largest survey of its kind to explore doctors’ knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding the human health benefits of pets. The 28-question survey was conducted in late August 2014 and had a margin of error of plus or minus 3.1%. The physicians in the survey had a median of 18 years of practice experience.

Among the survey’s key findings:

- Most doctors have successfully worked with animals in medicine.

69% have worked with them in a hospital, medical center, or medical practice to assist patient therapy or treatment. They report interactions with animals improve patients’ physical condition (88%), mental health condition (97%), mood or outlook (98%), and relationships with staff (76%). - Doctors overwhelmingly believe there are health benefits to owning pets.

Dr. Pan’s SCR 73 Establishes October 10th as Blue Light

CA STATE HR 28 JULY 15,15,HUMAN EDUCATION TO TEACH EMPATHY TO STOP

Government urges parents to limit their children’s social media use to TWO hours at a time

Government urges parents to limit their children’s social media use to TWO hours at a time

Kind Is The New Cool Anti-Bullying Stop Bully Novelty Shirt T-Shirt

PLEASE CLICK ON IMAGE TO LAUNCH TO AMAZON INFO.

BULLYING T-SHIRT

Bill Text - HR-28 - California Legislative Information - State of ...

https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov › faces › billNavClient › bill_id=2015201...

Jul 15, 2015 - HR-28 (2015-2016).

Sections 233.5 (part of the Hate Violence Prevention Act) and 60042 of the Education Code require instruction in kindergarten and grades 1 to 12, inclusive, to promote and encourage kindness to pets and humane treatment of animals; and

WHEREAS, Humane education, such as that involving wildlife, the animals’ place in the overall environment, and the negative impacts humans can have on them, including death and extinction, can disrupt the cycle of animal and human abuse by decreasing a child’s potential to be abusive or neglectful toward animals and, consequently, to promote prosocial behavior toward humans; and

WHEREAS, Humane education programs seek to prevent violence by teaching empathy, compassion, and respect for all living beings and help children develop into caring, responsible citizens; and TEACHING EMPATHY THROUGH DOG THERAPY (SEL) OFFERS GREATER OUT COME TO STOP BULLYING IN CONJUNCTION WITH ONLY A FLIP PHONE NO SMART PHONE.

BRADMAN UNVERISTY SEL DOG THERAPY SCHOOLS (pdf)

Government urges parents to limit their children’s social media use to TWO hours at a time

Government urges parents to limit their children’s social media use to TWO hours at a time

Government urges parents to limit their children’s social media use to TWO hours at a time

- 1 Feb 2019, 21:19

- Updated: 3 Feb 2019, 0:09

PLEASE NOTE THE BRIGHT WHITE EMITTING LIGHT

SWITCH OFF Blue Light Awareness Day by speaking to the health hazards posed by extended exposure to blue light from digital devices, in conjunction with World Sight Day.

https://sd06.senate.ca.gov › news › 2019-10-09-dr-richard-pan’s-scr-73-es...

Government urges parents to limit their children’s social media use to TWO hours at a time.

Chief Medical Officer Dame Sally Davies's formal guidelines come after content promoting suicide and self-harm was linked to death of Molly Russell, 14

CHILDREN should be limited to just two hours-a-time on social media – new official advice will declare next week.

In the first formal guidelines ever, the Chief Medical Officer will pile huge pressure on web giants to introduce a cut-off for under-18s.

Kids should then take “exercise breaks”. The move comes amid growing alarm at a generation hooked on social media.

Campaigners are likely to demand the crackdown – to be unveiled by Dame Sally Davies next Thursday – goes even further.

Research earlier this week found under-fives spend four hours and 16 minutes a day glued to screens - including online, ,gaming and TV.

Seven in ten of those aged 12 to 15 took smartphones to bed.

And a fifth of children aged 8-12 are on social media – despite supposed bans on under-13s. The new guidelines revealed by James Forsyth in today’s Sun follow an official request from Health Secretary Matt Hancock

The Tory high-flyer last weekend demanded social media giants remove suicide and self-harm material from their sites after the father of a 14-year old teenager blamed Instagram for her death.

Dr. Richard Pan’s SCR 73 Establishes October 10th as Blue Light Awareness Day in California

Government urges parents to limit their children’s social media use to TWO hours at a time

Dr. Richard Pan’s SCR 73 Establishes October 10th as Blue Light Awareness Day in California

More research shows the long-term health concerns associated with cumulative blue light exposure from our electronic screen devises; October 10th is also World Sight Day

October 9, 2019

SACRAMENTO – With more than 80 million electronic devices with digital screens in the state of California, and average screen time exceeding 9 hours per day, exposure to blue light has become a serious concern for public health. Dr. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), Chair of the Senate Health Committee kicks off Blue Light Awareness Day by speaking to the health hazards posed by extended exposure to blue light from digital devices, in conjunction with World Sight Day.

“The impact of high energy blue light emissions on children is a significant health concern,” said Dr. Richard Pan, pediatrician and State Senator. “The resolution, passed by unanimous and bi-partisan support in both the Senate and Assembly, demonstrates that when it comes to protecting public health and educating around emerging health concerns, California will take the lead.”

Today’s announcement comes on the heels of the California State Legislature’s passage of SCR 73, a resolution which outlines the growing body of evidence and scientific research related to the long-term health impacts of extended exposure to blue light from digital devices. Those devices include: computer monitors, phones and tablets, that, absent blue light reducing filters, project high levels of toxic blue light into consumers’ eyes. With the passage of SCR 73, The State of California encourages all its citizens, particularly children whose eyes are still developing, to consider taking protective safety measures in reducing eye exposure to high-energy visible blue light.

California State Senate and Assembly Health Committees began looking at the issue of high energy blue light emissions from digital devices and screens in 2018, and in particular, the increased usage of, and access to, digital devices by young children and adolescents whose eyes are particularly susceptible to long-term damage from blue light.

https://sd06.senate.ca.gov › news › 2019-10-09-dr-richard-pan’s-scr-73-es...

Oct 9, 2019 - With the passage of SCR 73, The State of California encourages all its citizens, particularly children whose eyes are still developing, to consider taking protective safety measures in reducing eye exposure to high-energy visible blue light.

Screen time 'may harm toddlers'

Florida kids are getting sent to psychiatric units under the Baker Act in record numbers

Dr. Richard Pan’s SCR 73 Establishes October 10th as Blue Light Awareness Day in California

The findings, published in the JAMA Paediatrics, suggest increased viewing begins before any delay in development can be seen, rather than children with poor developmental performance then going on to have more screen time. https://time.com/5514539/screen-time-children-brain/

What do the researchers think?

When young children are observing screens, they may be missing important opportunities to practise and master other important skills.

In theory, it could get in the way of social interactions and may limit how much time young children spend running, climbing and practising other physical skills

The American Association of Paediatrics' (AAP) guidelines on screen time say:

- For children younger than 18 months, avoid use of screen media other than video-chatting

- Parents of children 18 to 24 months of age who want to introduce digital media should choose high-quality programming, and watch it with their children to help them understand what they are seeing

- For children ages two to five years, limit screen use to one hour per day of high-quality programmes. Again, parents should be watching it with their children.

- For children ages six and older, place consistent limits, making sure screen time does not get in the way of sleep and physical activity.

The Canadian Paediatric Society goes further, saying screen time for children younger than two is not recommended.- although they may still eventually catch up.

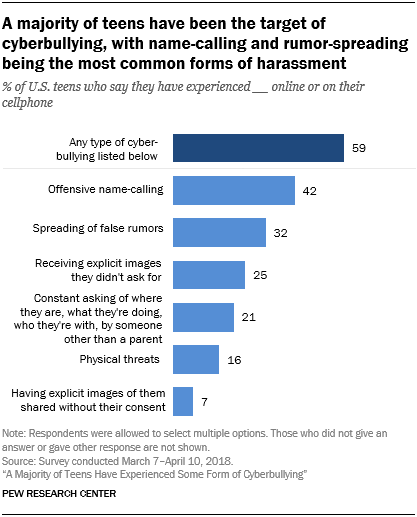

A Majority of Teens Have Experienced Some Form of Cyberbullying

Florida kids are getting sent to psychiatric units under the Baker Act in record numbers

Florida kids are getting sent to psychiatric units under the Baker Act in record numbers

PLEASE NOTE THE GIRLS FACE IS ILLUMINATED FROM BLUE LIGHT SCR 73 CA STATE WARNING OF EYES HARM,SLEEP ISSUES,TO MUCH SCREEN TIME ANYTHING OVER TWO HOURS PER ANY IN PREVENTING SUICIDES Resolution SCR-73 sponsored by Dr. Richard Pan, Chair of the California Senate Committee on Health was introduced on August 21, 2019 for the purpose of bringing public awareness to the growing body of evidence coming out from the medical community regarding the impacts of extended exposure to artificial high-energy visible (HEV) blue light emitted from consumer electronic devices. In addition to unanimous passage by the California Senate, the Blight Light Awareness Resolution for October 10, 2019, was ratified by the California Assembly on a vote of 70-0. https://sd06.senate.ca.gov/news/2019-10-09-dr-richard-pan%E2%80%99s-scr-73-establishes-october-10th-blue-light-awareness-day-california

59% of U.S. teens have been bullied or harassed online, and a similar share says it's a major problem for people their age. At the same time, teens mostly think teachers, social media companies and politicians are failing at addressing this issue.

Name-calling and rumor-spreading have long been an unpleasant and challenging aspect of adolescent life. But the proliferation of smartphones and the rise of social media has transformed where, when and how bullying takes place. A new Pew Research Center survey finds that 59% of U.S. teens have personally experienced at least one of six types of abusive online behaviors.1

Name-calling and rumor-spreading have long been an unpleasant and challenging aspect of adolescent life. But the proliferation of smartphones and the rise of social media has transformed where, when and how bullying takes place. A new Pew Research Center survey finds that 59% of U.S. teens have personally experienced at least one of six types of abusive online behaviors.1

The most common type of harassment youth encounter online is name-calling. Some 42% of teens say they have been called offensive names online or via their cellphone. Additionally, about a third (32%) of teens say someone has spread false rumors about them on the internet, while smaller shares have had someone other than a parent constantly ask where they are, who they’re with or what they’re doing (21%) or have been the target of physical threats online (16%).

Florida kids are getting sent to psychiatric units under the Baker Act in record numbers

Florida kids are getting sent to psychiatric units under the Baker Act in record numbers

Florida kids are getting sent to psychiatric units under the Baker Act in record numbers

Florida kids are getting sent to psychiatric units under the Baker Act in record numbers

Such evaluations have been outpacing child population growth statewide — and in regions like Southwest Florida, by leaps and bounds — for nearly a generation.

Frank Gluck, Fort Myers News-PressUpdated 12:56 p.m. PDT Aug. 22, 2019

Content warning: This story references incidents of self-harm.

Trouble started, as it often does, with a romantic rivalry.

One teenage boy, a student at Charlotte High School in Punta Gorda, warned his schoolmate, Solan Caskey, to stay away from a certain teenage girl in a series of Sharpie-penned messages on the school’s bathroom wall. Solan, being a teenage boy himself, impulsively responded with his own graffiti, including:

"Mother f---er try me," "She's mine, bitch" and "I accept to fight..."

The exact details of what happened immediately after this 2017 exchange are uncertain. But a day later, a police report shows that the school resource officer and a school psychologist concluded Solan was suicidal and possibly wanted to kill other students.

Solan denied this at the time (and still does), but the officer forced him to the ground and handcuffed him before taking him to Charlotte Behavioral Health Center in Punta Gorda for a potentially multi-day forced stay.

There, he got a mental health examination under the state's Baker Act — making his case one of a record 32,763 such evaluations of Florida children that year.

0:001:29ADSolan Caskey was Baker Acted twice and released as soon as his case was reviewed“They want to use the Baker Act for any behavioral problem — anything they don’t like," Hilary Caskey said.AMANDA INSCORE, AINSCORE@NEWS-PRESS.COM

Such mental health checks have been outpacing child population growth statewide — and in regions like Southwest Florida, by leaps and bounds — for nearly a generation.

In the last 10 years alone, they have more than doubled in Lee, Collier and Charlotte counties, far outpacing population growth. There are now more than 2,200 such cases involving children every year in this region.

Many see this as a sign of increased awareness of mental illness in children at a time when data show that suicidal thoughts and actions among those younger than 18 are increasing. Their increase also tracks with the rise of mass shootings in the United States, and a heightened awareness of that threat, particularly in schools.

But some parents, counselors and other mental health experts say the rapid increase in such forced examinations, which are designed for only those likely at immediate risk of harming themselves or others, suggests that the law is being used more as a disciplinary tool than a mental health aid.

And, they argue, taking kids into custody who are not actually suicidal or credibly threatening others’ lives – often in handcuffs and in the presence of their peers – may worsen conditions like chronic depression and anxiety.

Read more in this series: Explore the mental health crisis faced by Southwest Florida's kids

Read our editorial: How to address the rise in juvenile Baker Act committals in Florida

In Solan’s case, medical records show that a psychiatrist interviewed him the next day and determined he was not a threat.

District spokesman Michael Riley, citing federal student privacy regulations, refused to discuss this particular incident. He responded via email only to say that children receive Baker Act referrals at school to "protect the child from doing harm to themselves or others."

Solan’s mother, Hilary, doesn’t buy that. And she remains livid.

“They want to use (the) Baker Act for any behavioral problem — anything that they don’t like," Hilary Caskey said. "If you have any kind of outburst, if you have any kind of emotion whatsoever and you are not just an order-following automaton, they will Baker Act you.”

The Florida Mental Health Act of 1971, commonly referred to as the "Baker Act" in reference to the law's original sponsor, allows for voluntary or involuntary mental health evaluations of up to 72 hours for people who have mental illnesses and are considered an immediate threat to themselves or others.

The law and its many amendments over the decades were designed to bring a consistent process to treating individuals with mental illness and to set forth —and, thus protect — their civil rights.

But some question whether the nearly half-century-old law is living up to its original intent, particularly as it relates to children.

LESSEN SCREEN TIME ONE HOURS PER DAY FOR UNDER 2 NONE

US marine who rescued a stray dog after seeing it 'bouncing around a battlefield

Want to raise empathetic kids? Get them a dog.The unexpected developmental benefits of having a pet

US marine who rescued a stray dog after seeing it 'bouncing around a battlefield

US marine who rescued a stray dog after seeing it 'bouncing around a battlefield' during a gunfight in Afghanistan reveals how he smuggled the animal home - before his new pet saved HIM from post-traumatic stress

- Craig Grossi met his dog Fred while fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2010

- Grossi, a Purple Heart recipient, brought the dog back to the United States

- He revealed how Fred had helped to lift him out of post-traumatic stress

- Grossi has written a book called 'Craig & Fred,' a memoir about his service

Growing number of students using, abusing ADHD medication Adderall as 'study drug'

Want to raise empathetic kids? Get them a dog.The unexpected developmental benefits of having a pet

US marine who rescued a stray dog after seeing it 'bouncing around a battlefield

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/keep-it-in-mind/201701/is-social-media-increasing-adhd

please click on image to view https://www.psychologytoday.com

Is Social Media Increasing ADHD?

Is social media changing the way we pay attention to information?

With rates of ADHD diagnoses on the rise, it’s easy to point the finger to technology as the scapegoat. There is a fear that our brain is getting sidelined – that we can’t focus on talking to the person in front of us because of the constant demands on our attention by social media.

We used to use our attention like a spotlight—focusing on one thing at a time. I call this the Spotlight Brain.

But today’s world isn’t like that—we have to process information very quickly. It’s hard to use the Spotlight Brain to stay on top of it all the tweets, updates, and notifications. And sometimes we would miss out on noticing important information.

A classic psychology experiment illustrates this Spotlight Brain. Participants were showed a video of people passing a ball. They were asked to count the number of ball passes. Halfway through the video, a man in a gorilla suit stands among the ball passers.

At the end of the video, participants were asked if they noticed anything unusual. Because of the Spotlight Brain, many people did not even notice the man in a gorilla suit!

But social media has changed the way we use our brain. Now we use it like a floodlight—this allows us to work with more than one thing at a time. We can pay attention to multiple pieces of information. I call this the Floodlight Brain.

Want to raise empathetic kids? Get them a dog.The unexpected developmental benefits of having a pet

Want to raise empathetic kids? Get them a dog.The unexpected developmental benefits of having a pet

Want to raise empathetic kids? Get them a dog.The unexpected developmental benefits of having a pet

nise Daniels is a child development and parenting expert specializing in the social and emotional development of children.April 14, 2015 at 3:00 a.m. PDT

One of the greatest lessons of my life came from a dog. It was Christmas Eve, 1989, and our house was burning to the ground. As we stood in the snow in our jammies, our Newfoundland, Alfie, kept running back toward the house to make sure all the children were out and that everyone was safe. (We were, thankfully.) It was the most selfless, unconditional act of love I’d ever witnessed.

While hopefully not everyone’s experience will be that dramatic, pets can be invaluable at teaching families, especially children, “emotional intelligence,” or EQ—a measure of empathy and the ability to understand and connect with others. More than intelligence, EQ is the best indicator of a child’s likely success in school. In fact, kindergarten teachers have reported that EQ is more important than the ability to read or hold a pencil. And unlike IQ, which is fixed at birth, EQ can grow and be nurtured, and what better way than with a loving pet who is a gift to the whole family? Here are five ways in which pets can help children develop their EQ.

By developing empathy

One of the cornerstones of EQ is empathy, which should be taught and modeled starting in early childhood. A variety of research in the U.S. and U.K., including by the late psychologist Robert Poresky of Kansas State University, has shown a correlation between attachment to a pet and higher empathy scores. (This is hardly a new idea: Philosopher John Locke in 1699 was advocating giving children animals to care for so that they would “be accustomed, from their cradles, to be tender to all sensible creatures.”) The reason is obvious: Caring for a pet draws a self-absorbed child away from himself or herself. Empathy also involves the ability to read nonverbal cues — facial expressions, body language, gestures — and pets offer nothing but nonverbal cues. Hearing a kitten yowl when it wants to eat or seeing a dog run to the door when it wants to go outside get kids to think, “What are their needs, and what can I do to help?”

Can multimillion-dollar suicide awareness campaign lower Utah’s suicide rates?

New Chicago Public Schools policies may bar students from texting teachers, coaches — and vice versa

Want to raise empathetic kids? Get them a dog.The unexpected developmental benefits of having a pet

By Ashley Imlay, KSL | Updated - Sep 23rd, 2019 @ 4:12pm | Posted - Sep 23rd, 2019 @ 2:32pm

SALT LAKE CITY — In the battle against the nation’s rising suicide rates, Utah leaders and donors met Monday to announce a “historic,” multimillion-dollar campaign to change stigmas surrounding mental health in the state.

“We’ve all had a personal journey with this issue. All of us have been impacted in some way, whether it’s family members, friends, loved ones, people in our community who have been impacted by suicide,” Lt. Gov. Spencer Cox said outside the state Capitol. “And so while we recognize that the government can’t solve all of our problems, there’s a critical role for government to play in this space.”

Two years ago, the Utah Department of Health released a report stating that teen suicides had increased 141% since 2011. A suicide prevention task force was then formed, Cox said. The idea for the campaign came out of that task force.

Last year, the Legislature provided $700,000 for the campaign if the public sector matched that amount in donations. Another $300,000 from the general fund was available for the campaign and did not require a match, Cox said.

Can multimillion-dollar, multi-agency suicide awareness campaign lower Utah’s suicide rates?

New Chicago Public Schools policies may bar students from texting teachers, coaches — and vice versa

New Chicago Public Schools policies may bar students from texting teachers, coaches — and vice versa

Can multimillion-dollar, multi-agency suicide awareness campaign lower Utah’s suicide rates?

Private sector meets match requirement to fund $2 million statewide campaign

Government, health, civic and church leaders walk out of the state Capitol prior to a press conference to announce the achievement of a private match donation for suicide prevention in Utah at the state Capitol in Salt Lake City on Monday, Sept. 23, 2019. Scott G Winterton, Deseret News

SALT LAKE CITY — In the battle against the nation’s rising suicide rates, Utah leaders and donors met Monday to announce a “historic,” multimillion-dollar campaign to change stigmas surrounding mental health in the state.

“We’ve all had a personal journey with this issue. All of us have been impacted in some way, whether it’s family members, friends, loved ones, people in our community who have been impacted by suicide,” Lt. Gov. Spencer Cox said outside the state Capitol. “And so while we recognize that the government can’t solve all of our problems, there’s a critical role for government to play in this space.”